Post by Zack Fradella on Jun 26, 2008 16:34:04 GMT -6

I put this is in here since Scott and I both had no clue what this was when we were storm chasing. In the evening hours on one of our chase days we saw this huge radar echo that looked like an explosion. The echo was like a storm blowing-up but then it shot out in all directions. We both joked around saying it was the government trying out their new nukes. Well, today I figured out what it was.

www.spc.noaa.gov/coolimg/batrad/javaloop.htm

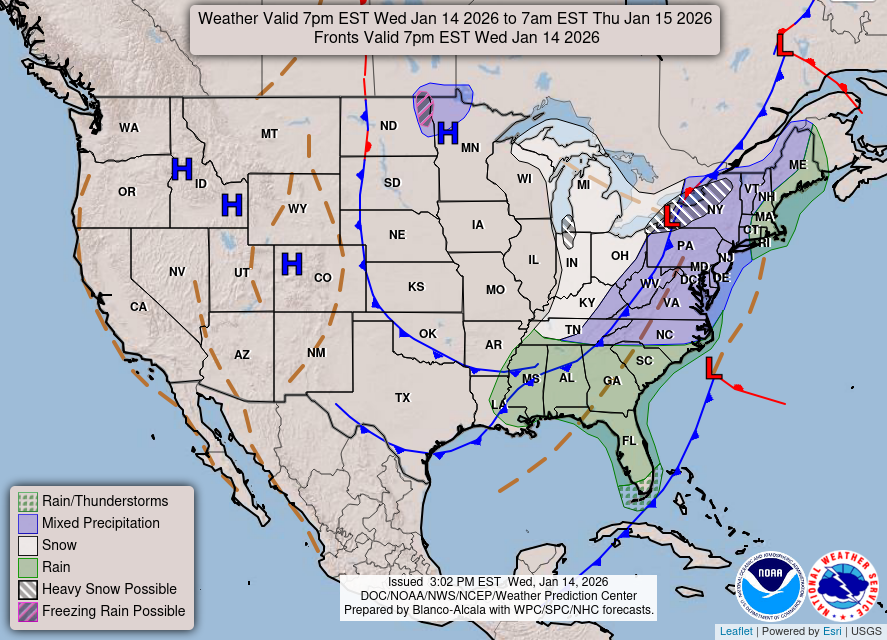

South Texas can become a BATtleground of nature: bats, that is, caught up in the environment around a large and dangerous thunderstorm. This happened in the early evening of 19 March 2006, as part of a swarm of bats was overtaken by a tornado-warned supercell over eastern Val Verde County and southwestern Edwards County.

Numerous caves dot the thick limestone beds of the Edwards plateau in South Texas. A couple dozen of them house about 100 million free-tailed bats from spring through autumn, according to the Texas State Handbook. Every evening during those seasons, the bats leave their daytime, underground refuges and take to the skies for a mass feast on flying insects. On radar, bat swarms in south-central Texas commonly appear as expanding rings or donuts during late afternoon and early evening, their collective echoes diffusing as they fly upward and outward from their cavernous homes.

On this evening, the bats swarmed out as usual from a cave between Carta Valley and Rocksprings, seemingly unaware that a severe thunderstorm had formed suddenly in the foothills of the Serranias del Burro range in Mexico, about 60 nautical miles to their southwest. The storm quickly crossed the Rio Grande into the Texas, struck rich moisture and instability, and began to rotate. As many supercells do, it then made a right turn -- straight at the southern part of the expanding horde of bats (see the accompanying radar reflectivity loop and the pair of storm-relative motion images). Radar from Del Rio detected both the storm and the bat swarm, and documented their interaction. This probably was not a favorable deal from the perspective of the bats.

At a minimum, many thousands of bats who were unable to circumnavigate the severe supercell had to have had an unpleasant ride. Did they find suitable shelter somehow before it was too late? What became of those bats who were sucked into the updraft region of the storm, or who may have encountered large hail in either the forward flank core, vault region or hook? Granted, these flying mammals doubtlessly have been coping with sudden weather changes for a very long time. Unfortunately for any given individual, it probably doesn't deal with a storm like this -- timed exactly to intercept the first night foray -- very often in its short lifetime. It is hard to imagine that the Bat-eating Supercell didn't cause a large casualty toll on part of their group.

www.spc.noaa.gov/coolimg/batrad/javaloop.htm

South Texas can become a BATtleground of nature: bats, that is, caught up in the environment around a large and dangerous thunderstorm. This happened in the early evening of 19 March 2006, as part of a swarm of bats was overtaken by a tornado-warned supercell over eastern Val Verde County and southwestern Edwards County.

Numerous caves dot the thick limestone beds of the Edwards plateau in South Texas. A couple dozen of them house about 100 million free-tailed bats from spring through autumn, according to the Texas State Handbook. Every evening during those seasons, the bats leave their daytime, underground refuges and take to the skies for a mass feast on flying insects. On radar, bat swarms in south-central Texas commonly appear as expanding rings or donuts during late afternoon and early evening, their collective echoes diffusing as they fly upward and outward from their cavernous homes.

On this evening, the bats swarmed out as usual from a cave between Carta Valley and Rocksprings, seemingly unaware that a severe thunderstorm had formed suddenly in the foothills of the Serranias del Burro range in Mexico, about 60 nautical miles to their southwest. The storm quickly crossed the Rio Grande into the Texas, struck rich moisture and instability, and began to rotate. As many supercells do, it then made a right turn -- straight at the southern part of the expanding horde of bats (see the accompanying radar reflectivity loop and the pair of storm-relative motion images). Radar from Del Rio detected both the storm and the bat swarm, and documented their interaction. This probably was not a favorable deal from the perspective of the bats.

At a minimum, many thousands of bats who were unable to circumnavigate the severe supercell had to have had an unpleasant ride. Did they find suitable shelter somehow before it was too late? What became of those bats who were sucked into the updraft region of the storm, or who may have encountered large hail in either the forward flank core, vault region or hook? Granted, these flying mammals doubtlessly have been coping with sudden weather changes for a very long time. Unfortunately for any given individual, it probably doesn't deal with a storm like this -- timed exactly to intercept the first night foray -- very often in its short lifetime. It is hard to imagine that the Bat-eating Supercell didn't cause a large casualty toll on part of their group.