Four tornadoes hit Moore, Oklahoma, in 16 years. Bad luck?

Nov 18, 2016 5:44:14 GMT -6

99lsfm2 likes this

Post by Briella - Houma on Nov 18, 2016 5:44:14 GMT -6

fivethirtyeight.com/features/tornadoes/?ex_cid=538twitter

Nobody knows how likely it is that a given town would be hit by four violent tornadoes in 16 years; if we knew that, then we’d also know whether Moore really is especially tornado prone, or just suffering a streak of bad luck. But we do know big tornadoes, themselves, are rare. Devastating EF4s made up 1.37 percent of all the tornadoes that hit the U.S. from 1994 to 2012.2 Just 0.14 percent were incredible EF5s.

And that’s enough to make Moore’s recent history turn heads. People who live in the Plains states, as I once did, have a special relationship with tornadoes, wary but familiar, like your grandma’s dog that’ll bite if you aren’t careful. This is a part of the country where little kids dream about growing up to be storm chasers. Where tornado sirens go off every Wednesday at lunchtime, just as a test of the system. It’s a part of the country where art professors like my dad duck outside for a peek at one of the most powerful tornadoes in recorded history.

But this thing with Moore even weirds out Oklahomans. “For years people have asked me, ‘What about Moore?’ ” said Gary England, a retired TV meteorologist who shepherded generations of Oklahomans through more than 40 tornado seasons. “People talk about topography. They talk about geomagnetic forces. I think it’s very unusual. But I think most scientists would probably tell you it’s just a roll of the dice.”

And that’s enough to make Moore’s recent history turn heads. People who live in the Plains states, as I once did, have a special relationship with tornadoes, wary but familiar, like your grandma’s dog that’ll bite if you aren’t careful. This is a part of the country where little kids dream about growing up to be storm chasers. Where tornado sirens go off every Wednesday at lunchtime, just as a test of the system. It’s a part of the country where art professors like my dad duck outside for a peek at one of the most powerful tornadoes in recorded history.

But this thing with Moore even weirds out Oklahomans. “For years people have asked me, ‘What about Moore?’ ” said Gary England, a retired TV meteorologist who shepherded generations of Oklahomans through more than 40 tornado seasons. “People talk about topography. They talk about geomagnetic forces. I think it’s very unusual. But I think most scientists would probably tell you it’s just a roll of the dice.”

The first big tornado recorded in Oklahoma happened on April 25, 1893. Witnesses claimed it was more than a mile wide. It hit Moore, which had just been incorporated that same year. Yes, one of the first things that happened in the town was the destruction of the town.

Brooks analyzed the data to find the times of the year and places in the country where tornadoes seemed to be more likely to happen. It wasn’t exactly a prediction of the future – more a detailed observation of the past. Using this, he came up with the most likely place and time for a big tornado: a town called Pauls Valley, Oklahoma, on May 2.

“So, has a tornado ever hit Pauls Valley on May 2?” I asked him.

“No. I don’t think so,” he said.5

But when I laughed, he explained. That location comes with a caveat. It’s got some built-in margin of error to make up for all the poorly collected reports and missed tornadoes of decades past. Scientists call this smoothing the data, and Brooks’ estimate is smoothed to within 50 miles or so.

Moore is 46 miles north of Pauls Valley.

Brooks presented this data at a conference on April 30, 1999. Three days later, the Bridge Creek-Moore tornado came to town. “In some sense,” he said, “That tornado on May 3 was about as likely of a violent tornado as you could imagine.”

“So, has a tornado ever hit Pauls Valley on May 2?” I asked him.

“No. I don’t think so,” he said.5

But when I laughed, he explained. That location comes with a caveat. It’s got some built-in margin of error to make up for all the poorly collected reports and missed tornadoes of decades past. Scientists call this smoothing the data, and Brooks’ estimate is smoothed to within 50 miles or so.

Moore is 46 miles north of Pauls Valley.

Brooks presented this data at a conference on April 30, 1999. Three days later, the Bridge Creek-Moore tornado came to town. “In some sense,” he said, “That tornado on May 3 was about as likely of a violent tornado as you could imagine.”

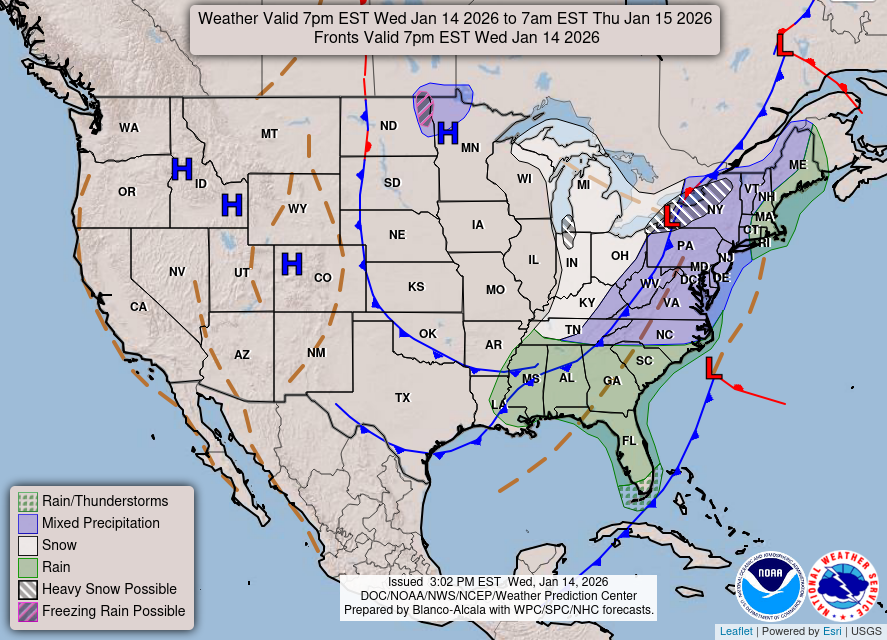

Broyles and Crosbie drew a frequency map of the 979 big tornadoes to touch down in 123 years, showing the number of tornadoes per 1,000 square miles. Plotted out this way, they found clusters. There are dark blobs – tornado alleys within tornado alleys – scattered across the continent. One of those blobs sits over central Oklahoma, north of the Canadian River, stretching from Oklahoma City to Tulsa. Moore is a part of that blob. Other places, including Fillmore County, Nebraska, and Union County, Mississippi, appear to be even more prone to big tornadoes.

They tested out some new ways of accounting for flaws in historical records and calculated the probability that these mini-alleys occurred randomly was just 3 percent. In October of 2015, they presented the results as a poster at the National Weather Association Annual Meeting. Their conclusion: “At least some of the mini-tornado alleys likely are real.” Potvin now thinks that may be a bit premature to say and there are a lot of caveats that go with it, but he is confident they aren’t just a relic of the sampling: garbage data produced by flaws in the way the tornadoes were documented and categorized. What’s happened in Moore is shaped by chance — but it’s also, probably, more than that.

Take the case of Codell, Kansas. On May 20, 1916, Codell was hit by a tornado. It was hit again on May 20, 1917. On May 20, 1918, a third tornado tore through town. Yes, really. You can find the records with the Kansas State Historical Society. Was there something special about Codell? Maybe. And then again, maybe not.

“What I really would like to know is what it was like on May 20, 1919,” Brooks said. “That’s the story I want. But we don’t really know much. I guess the 1918 tornado just sort of ended the town.”

And after that, Codell, or what was left of it, was never hit by a tornado again.

“What I really would like to know is what it was like on May 20, 1919,” Brooks said. “That’s the story I want. But we don’t really know much. I guess the 1918 tornado just sort of ended the town.”

And after that, Codell, or what was left of it, was never hit by a tornado again.